Interview by Jim Mora of Radio New Zealand on the National Radio “Afternoon” show of 28 January 2007.

Jim Mora: What were the “golden years” – how do you define them?

Emmanuel Makarios: I guess they were the years after the Second World War when shipping was entering a new era after having gone through those terrible years of war and there was a lot of new tonnage being built and of course the conditions were improving on ships and they became an interesting way to earn a living - seafarers could work theirr way around the world seeing all these wonderful places. Anyone you speak to from my period at sea or even before that all think of that period between the 1950s through to say the late 1970s as being the best years, because seafarers had good conditions, they had good rates of pay and they were going to wonderful places; whereas before that they either had to endure the risk of torpedoes or the conditions at sea were pretty harsh – you probably wouldn’t want your dog to live in those sorts of conditions!

JM: Yes they would make those years comparatively golden [laughs]. Now your book contains 288 wonderful colour images of New Zealand maritime scenes – where are they from?

EM: Principally from collection the Museum of Wellington City and Sea which has an extensive maritime collection. When I was working at the old Wellington Harbour Board Maritime Museum I used to see a lot of these slides come through the door and they were processed and put away and I’d forgotten a lot about those images over the years. The book really came about almost by accident – I had to do some research out at the museum’s store one day and I suddenly rediscovered these wonderful images. There’d be equally wonderful collections but mostly in private hands; this would be probably the best public collection. So the book really developed from there.

JM: I should really ask just while it’s in my mind and before we get into the book itself, Emmanuel – do you see a second golden period for shipping with the government’s promise of greater emphasis on freight by sea in the future?

EM: It’d be wonderful to think that might be the case, but there are a lot of different factors now. Ships are much faster now, the turnaround period in port isn’t very long so seafarers don’t get a chance to develop those relationships that they might have with people ashore and the possibility to go around looking at the different sights that might be seen. Today it’s very much a case of you’re at sea and you’re in port for half a day, or a day at best and you’re away again. So I think those romantic days of seafaring are gone and I don’t think we will ever see them again.

JM: Good point. Well let’s just talk a bit about the romance. In the old days you headed overseas, didn’t you, on passenger liners?

EM: Exactly

JM: Not planes.

EM: Not planes. A few did travel by air of course but it was very expensive. For the majority of people if they were heading to the UK on their big OE they would get on one of the Shaw Savill line ships like the Northern Star or the Southern Cross or they may have travelled on one of the New Zealand Shipping Company vessels such as the Rangitoto or the Rangitata and their adventure would begin when that last mooring line was let go in Wellington or Auckland or wherever they were departing from in New Zealand. And they had a month or six weeks of excitement ahead of them. I guess that going to new places, and for a lot of them it would have been their first trip overseas, would have been a just wonderful experience. Of course there is a bit of a mundane period at sea as well, but you put those times to good use by reading or relaxing. But nowadays you’re herded onto a tin can, you’re buckled into your seat and off you go. Before you know it you’re in London and sort of wonder how the heck you got there. By sea travel it all seems to fall into place and makes some sense to you [laughs].

JM: Yes and that’s an important distinction, it was a journey you participated on and had cognisance of and experienced fully.

EM: Exactly

JM: So the big tin cans changed that aspect of travel by sea and containerisation changed the other?

EM: Absolutely. That was a huge change in how cargo was handled in most cases. It was a concept that started to be thought of and developed in the late ‘50s, early ‘60s but it didn’t start to take off until about the mid to late ‘60s and not in New Zealand until the very early ‘70s. It certainly changed some of that romance at sea from that point on. Instead of you arriving in Wellington on the Shaw Savill and Albion Line cargo vessel the Delphic, for instance, and you might be berthed in Wellington for two or three weeks, and then you’d leave from here and you might head down to Lyttelton, and you might be there for another week – and these ships might spend months on the New Zealand coast – and from a ship owners’ and manufacturers’ or importers’ point of view you can understand them not being happy about having ships sitting around costing them lots of money – but from the point of view of the seafarer it was a wonderful time. And a lot of British seamen ended up marrying New Zealand women, eventually making their way back to New Zealand and settling here and ending up working on the waterfront or shipping out on New Zealand vessels. So there was a real culture there and you asked before if the golden years can be relived – I don’t really think so, that culture is gone. Maybe to a small degree it could be revisited but when I say the golden years it really was that period.

JM: The 19th of June 1971. Not to be too hyperbolic about it, but was this a day when the shipping business changed forever?

EM: I think so. It was the beginning. I think a lot of us didn’t imagine that containerisation would change things quite so drastically or maybe quite so quickly. It not only changed life for seafarers but it changed life for people working on the waterfront, watersiders. The whole concept of cargo handling changed and I suppose some watersiders probably said ‘good job’ because [conventional handling] was backbreaking work. I know a lot of people have a view of watersiders thinking ‘these guys never worked’ but these ships got loaded somehow and somebody had to do it. So I guess for them maybe, the advent of mechanisation with boxes meant that things could be loaded onto a ship with far less handling, which meant that in terms of their physical well-being they probably lasted a few more years. But from the point of view of enjoying seafaring it did change because as much as a seafarer enjoys their time at sea they also enjoy their time in port and if you’re not going to be spending as much time in port then it starts to defeat the purpose.

JM: That day I mentioned when the container ship Columbus New Zealand arrived at Wellington, an historic day, were the changes foreseen, did everybody stand on the dock and applaud or did people see what was going to happen in terms of what we lost?

EM: I suspect so, certainly the Harbour Board would have been there applauding and members of government would have been there and some of the trade unions probably had representatives there to be part of that event. But I think anyone who was in the industry both afloat and on the waterfront probably would have thought about it and may have had a slight anxiety in the pit of their stomach thinking ‘well is this the thin end of the wedge?’ But a lot of people probably didn’t worry too much because we’re talking about the beginnings of these vessels coming here, the ports were still full of conventional ships - and when I say conventional ship it’s a cargo ship of the type which has its own cargo gear and the ships described in this book are conventional ships – so when they looked around themselves and saw these ships still there they probably had a false sense of security. But certainly by the mid ‘70s it was becoming evident that these were the ships of the future and the old girls that used to come out here – the old ‘home boats’ as they were referred to – were becoming fewer and fewer.

JM: So as the ‘golden era’ ended another factor in that equation was presumably the entry of Britain into the EEC in 1973?

EM: Absolutely, that had a huge impact on New Zealand. Britain was taking 40% of our agricultural exports, we were the bread basket, basically, of the UK. When that changed you saw fewer British ships coming out here, although the British companies earned their way into that service and some of them survived, they combined and reinvented themselves and introduced services to other parts of the world as New Zealand’s trade developed new markets. But British flags became fewer and fewer and as time has gone on most companies fly a flag of convenience for tax purposes, so to see a British flag in a port nowadays is a sight to behold really.

JM: Why was the once powerful and very famous Union Steam Ship Company unable to keep up with the changing face of the industry because it finally went under didn’t it?

EM: It did. It was established in 1875 so it was around for a long time and they did change over the years. They were the biggest shipping company in the southern hemisphere for a time and they had a huge fleet of ships and fingers in many pies. A lot of the coastal shipping companies that operated around New Zealand and even Australia might have been operating under their own names but were 51% owned by the Union Company. They were a huge organisation and they’ve been referred to as ‘The Southern Octopus’ because they had a tentacle in every shipping company operating around this part of the world. But I think what ultimately what killed them was that for many years they had the protection of operating their vessels on the trans-Tasman service between New Zealand and Australia with almost a guarantee that they would be carrying any cargoes that would be crossing that stretch of water. Some years ago now and I can’t tell you exactly when but it’s not that long ago the government changed the rules and opened up the coast basically and enabled anyone to come in and operate in that area and as I said earlier a lot of shipping companies fly a flag of convenience which means they can operate with third world crews who are quite happy to be paid a few dollars a day and there’s just no way you can compete against that type of policy. So for the Union Company that was really the death blow. But having said that they were around for a long time, they were around for as long as some of the famous British companies that used to trade out here. They were a fantastic employer for many New Zealanders and I saw a figure recently, I don’t remember it exactly off the top of my head but they employed a huge number of New Zealanders both afloat and ashore because as I said the company was involved in all kinds of things. I remember when I was at college spending all my spare time on the waterfront and befriending different people I managed to score myself a job as an office boy in the head office of the Union Company here in Wellington during my school holidays and that was a huge thing for me. I remember going back to Rongotai College where I attended and the teacher would ask different students “what did you do this holiday, Jimmy ?” and they would say “I washed bottles” or something and then they’d come to me and I’d stand up and push my chest out and say “I worked for the Union Company, sir” and it was really a big deal and for me especially because it was a stepping stone in the right direction in getting me to sea. Even though I wasn’t totally immersed in the culture I felt the effects of it and it was really drawing me to wanting a career at sea.

JM: Everybody travelled on the three big deal ships, the glamour service ships the overnight ferries between Wellington and Lyttelton didn’t they? The Hinemoa, the Rangitira and the Maori, were they the big three?

EM: They were, there was the ill-fated Wahine

JM: yes later on

EM: which came later in the piece and then the final Rangitira. Yes they were and I always thought of them as the poor-man’s cruise really because it was an overnight trip and anyone who remembers that service or travelled on it will remember the streamers and the toilet rolls and what have you that were thrown ashore and connected to loved ones ashore from those on board, you thought you were going off to the UK [laughs]. It was a fantastic thing and for a lot of us that was our first taste of going to sea and the joys maybe of travelling on a passenger ship. Anyone travelling on that took it very seriously, the streamers really reflected that I thought.

JM: Yes and everyone I presume, Emmanuel, was on board; you would have seen everyone from school parties and family groups to MPs and famous New Zealanders.

EM: Exactly, they were an important part of the transport system of New Zealand right up to the ‘70s. Unfortunately the service ceased in 1976 when the Rangitira was withdrawn from service. She’d been heavily subsidised by the government for a long while and it just wasn’t viable but I think a lot of that was due to the rail ferries that the government had introduced for running between Wellington and Picton which meant you had a ferry leaving here every few hours and for anyone travelling to Christchurch and beyond it was quicker for them to jump on one of the Picton ferries and drive than to wait all day and then travel all night to get to their destination and then have to drive on from there. And cheaper airfares, all those things took their toll on that service. But it was around for a ferry long time, it was established in the late 19th century so it was a very big part of what the Union Steam Ship Company provided. It was a sad day when that service ended. I think anyone who was around in those days will have some fond memories - some may have not so fond memories depending on the weather they experienced on the voyage!

JM: So the ports must have been exciting places to be comparatively during the ‘60s and early ‘70s?

EM: Absolutely, if you were living in a port or a harbour city you were naturally drawn to the port and you didn’t have to be a ship enthusiast or someone who necessarily wanted a career at sea, but they were nice places to stroll on a Sunday afternoon and you’d often see families wandering along the waterfront , taking in some fresh air, taking in some sunshine. I guess we were a little less sophisticated in those days, and I don’t mean that in a harsh way, it was just the way we were. We didn’t have the cafe crowd we have now so people tended to have to entertain themselves a lot more and the waterfront was one of those things you could do at no cost.

JM: You had access too, that’s the other big difference.

EM: Exactly, the waterfront belonged to the people because all the boards were public bodies, they were elected, it was something that the average Joe Bloe could have a say in if he wanted to participate. They could get entry at any time of the day and night, the gates were never locked. I can understand some of the concerns today with health and safety but as I said earlier I kicked around the waterfront from about the age of 9 and we used to fish and ride our bikes from one end of the port to the other and explore and often get told off if we were doing something that we shouldn’t be but generally I think we were all reasonably safe, I don’t recall any tragedies but there could well have been. But we certainly weren’t wrapped up in cotton wool like society tends to be today.

JM: What’s your favourite photo in the book?

EM: My favourite photo is of a young boy who is standing at the edge of a wharf leaning against a bollard, he’s got one hand on his pushbike, he’d probably be about 10 years of age. It was taken in the late’50s and he’s observing this little coaster called the Kuaka which is just preparing to sail, she’s heading off to Picton to load meat to bring back to Wellington to put onto a ‘home boat’ to head back to Britain. I look at that photo and he could be me, that’s exactly what I did. You would stand there looking in awe at these vessels coming and going. They were sailing at all hours of the day and night and you’d stand there and just observe, and for someone like me who passionately wanted to go to sea, you were thinking to yourself when is my time going to come to be able to get onto a ship like this and start working. I never had a favourite, it wasn’t as if I only looked at the big ships, it didn’t matter what it was, I always found them fascinating. The interesting thing is that a couple of people I know who are maritime people still involved in the industry have rung me to congratulate me on the book which is really nice and it was interesting that both of them picked up on that photo and said exactly what I’ve just said. That’s what I was hoping, I was hoping that people would see it my way. Most people who have gone to sea cut their teeth by playing on the waterfront and by talking to seafarers and talking to watersiders.

JM: They were small boys watching the Kuaka berth at Wellington.

EM: That was it, that’s what we did, we sat there in awe and dreamt of the time when we might go away.

JM: Lovely to talk to you, thank you, we have to go but it’s been a pleasure.

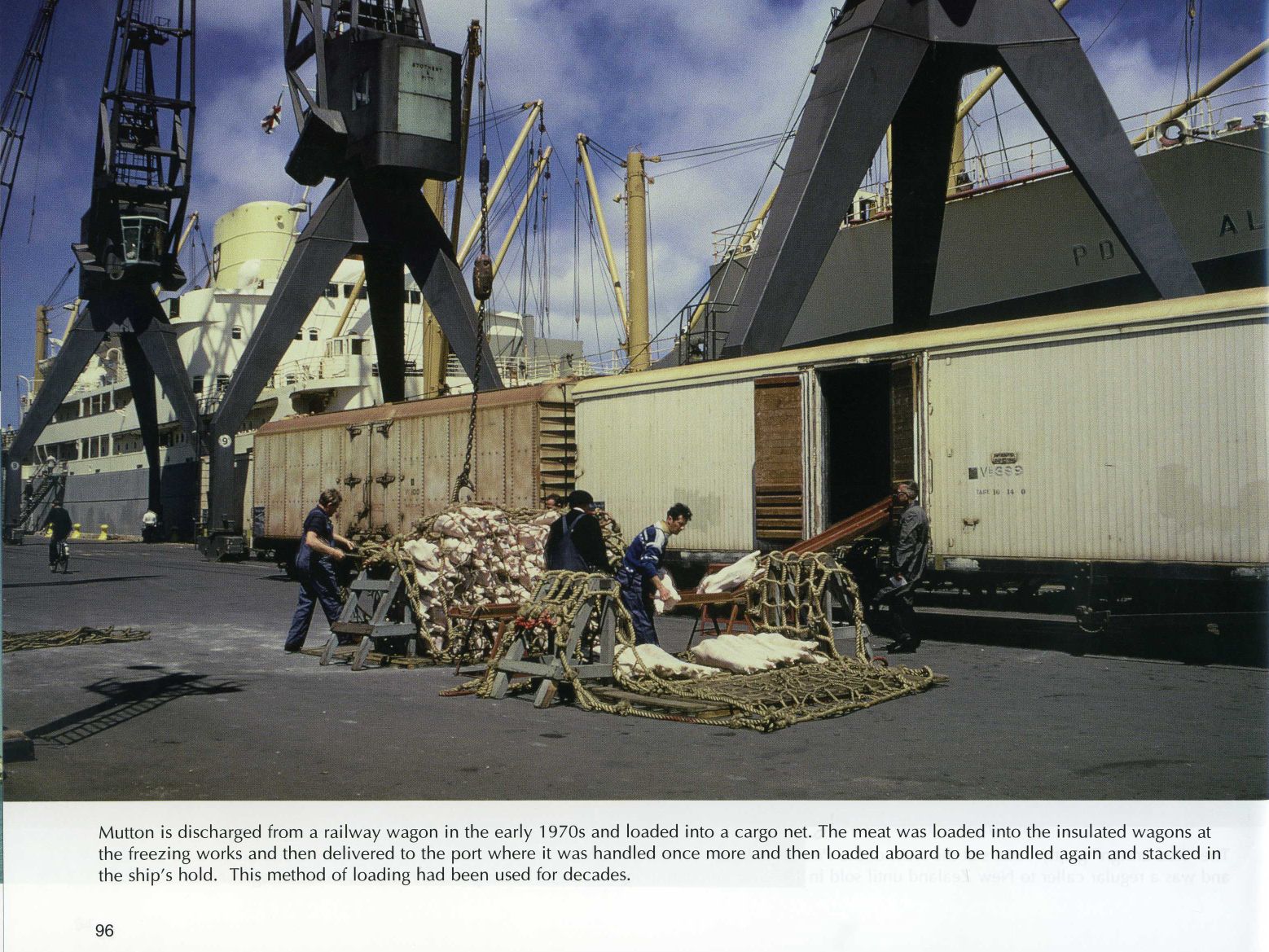

Times have changed hugely: in the golden years boys could bicycle around the wharves gazing at the fascinating sights of shipping while frozen meat and other primary produce for the UK was loaded onto a British ship (page 96 in the book). Today all is prepacked into containers which are speedily loaded on and off ships that are not so easy on the eye - and the public are barred (webcam in Centreport Wellington).

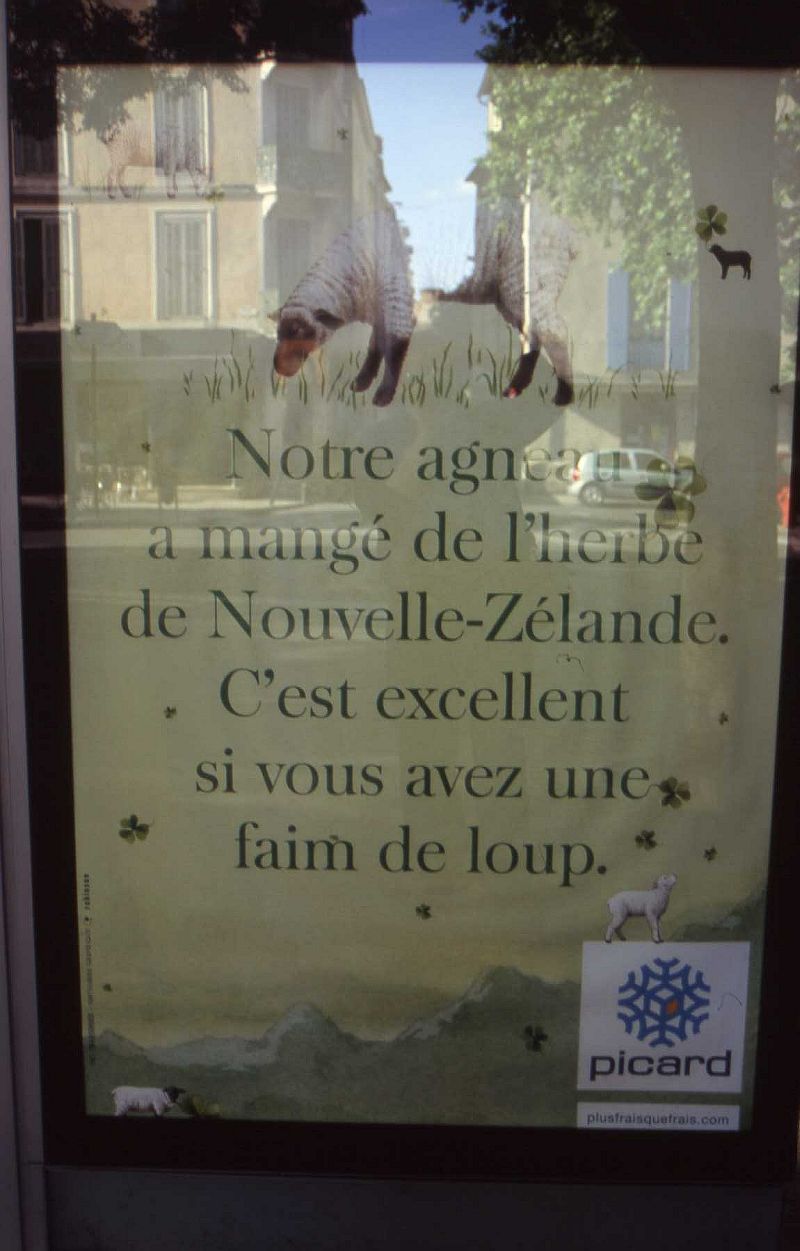

The origins and destinations of merchandise have changed hugely too. In 1955 no less than 65% of New Zealand's exports went to Britain, France was in second place with 6%. The advent of the EEC in 1957 changed that particularly after Britain joined at the beginning of 1973 when the focus had to switch to exporting elsewhere. In 2005 only 4.7% of New Zealand's exports went to Britain and France wasn't in the top ten, despite marketing efforts like this billboard seen in Nimes in 2007. (Geoff Churchman photo)